ABSTRACT

This article aims to overcome the empirical limitations of tourism studies concerning customer experience, to focus on the transformations of work activity. From an ergonomics perspective focusing on work activity in two hotels, the article proposes an analysis about smart technologies based on a case study of a chatbot or conversational agent (CA) and proposes an alternative to implement technology in work design. This study uses a systemic approach and incorporates semi‑structured interviews, UX curves with different stakeholders (N=7) from touristic organisation: strategic, operational and design workers. Results show that the different stakeholders do not share the same representation of chatbots. Designers and strategy workers consider the technology as a way to improve the customer experience and reduce work constraints by eliminating tasks and creating a new tasks redistribution . Furthermore, the use of chatbot reveals greater flexibility for the operational staff. We also note reconfigurations of work for both staff and designers in order to allow chatbot evolutivity and efficiency over timeIn the light of these statements, this research shows that the deployment of technology cannot be successful without a comprehensive analysis of the work activity context. This study also highlights the role of human intelligence in the creation of evolving and contextually adapted tourism systems. From a general point of view, the introduction of technologies has led to a profound reorganisation of the stage and backstage tasks. They can also be deleterious to work and service relationship when the conditions of their implementation are not thought out in advance. The article suggests to design these work systems through a human-centred approach by contributing to the development of Artificial Intelligence (AI) technology at the service of humans and their work.

CCS CONCEPTS

• AI conversational agent • Human centred approach • Work activity

KEYWORDS

Chatbot, Artificial Intelligence, Ergonomics, Work Design, Hospitality sector

ACM Reference format: Flandrin Pierre, Hellemans Catherine, Van der Linden Jan, van de Leemput Cécile 2021. Emerging technologies in hospitality: effects on activity, work design and employment. A case study about chatbot usage. In l’Interaction Homme-Machine à la Relation Homme-Machine, comment concevoir des systèmes performants et éthiques, ACM Ergo ’IA 2021, Biarritz, France.

Introduction

Over the last few decades, the tourism sector has become one of the most important drivers of global economic growth and development, as well as a major contributor to global employment. Like other sectors, tourism and hotel organisations are massively engaged in digital transformation [1]. Tourism sector is constantly evolving and currently facing a new era, closely linked to the development of digital data and the arrival of Artificial Intelligence (AI) [2,3]. From a customer experience point of view, emerging and smart technologies have enabled the development of new ways of interacting with customers and are offering new service experiences [4-6]. Smart technologies have spread into the hospitality and tourism industry, from underlying technologies such as the Internet of Things (IoT), big data, speech and facial recognition, virtual reality, augmented reality to intelligent service desks and service robots [7, 8]. For instance, some hotels (like the Henn-Na hotel in Japan) innovate with fully automated robotic staff at the reception desk (Figure 1). Customers have no contact with a human employee during the entire service experience. From a work point of view, automated hotel experiences reveal that social capital is not anymore considered as the main factor of differentiation, customer personalisation, and competitive advantage [9], as hotels without any human activity attest [10]. However, these experiences have been criticised due to too many robots’ failures [11]. For example, the AI assistant “Churi” woke up a sleeping guest several times in one night because it mistook the guest’s snoring for a command [11]. In fact, automation is still only a utopian vision for tourism, as human workers play a predominant role in the activity of these intelligent systems. Moreover, service activities have never been so demanding: immediacy, speed, flexibility, sometimes obliging workers to act without a prescribed framework [12].

Simultaneously with the development of service automation, we witness the development of “click workers” [13] who are responsible for powering, supervising, and ensuring the technology flexibility, as well as the “building machine understanding” [14]. This technological implementation and uses raise questions about the transformations of organisations, work situations and service relationships. The hospitality workers activities are being reshaped by technologies redrawing the structure of their job. The covid‑19 crisis has notably accelerated the trend towards mediating technologies.From an ergonomics perspective, this paper focuses on work activity in two hotels and proposes a reflection about smart technologies usage. Based on a case study about chatbot usage, our data tend to establish an alternative implementation model. The “Artefactualisation”[1] of activities is still marginally discussed in a major sector as tourism. In this context, this research aims to understand the potential consequences of chatbot use on workers activities and to propose a reflection about work design. As Morin (2015) [15], we consider that comparing machines and humans’ abilities may lead to the creation of work design systems that are not adapted to the complexity of workplace situations. Therefore, a question arises: can emerging technologies be considered as social innovation, in the sense of « functional ideas, new practices, procedures, rules, approaches or institutions introduced to improve economic and social performance » [16], and thus be considered as a progress in the organisation of work? Could a reconsideration of the work design be triggered with the increased adoption of smart technologies?

- 1. Smart technology in touristic sector

Artificial intelligence is being increasingly seen as technology packages that produce many benefits in terms of performance (optimisation of internal processes, speed of task execution, increased productivity, etc.), and in terms of facilitating work or even reducing drudgery by allowing the automation of tedious or repetitive tasks [17]. Indeed, tourism sector is increasingly investing in emerging technologies known as “intelligent” and identified as “major innovations that break with known practices and generate significant impacts in the environment where they will be deployed” [18,19]. They are perceived as “intelligent » because they can show a form of “intuition” aimed at solving problems, as an algorithmic program, that would require humans to use their cognitive abilities [17]. They are also considered as interconnected systems, and able to improve human skills in information retrieval or decision-making. The AI‑based technologies are able to perform new functions [20] such as: optimisation, prediction, matching, detection, recommendations or even decision-making [21].Tourism practices are transformed both with human personalisation and with the use of mediating technologies. In the tourism sector, technology use main purposes are the search for massive data through information systems (IS) and the capacity to predict customer flow to set price recommendations. Finally, in the context of customer interactions, some tasks are now entrusted to interaction assistants (e.g., conversational agents). A new service is thus emerging: an automated, intelligent and contactless service reinforced by distancing gap imposed by the covid‑19 crisis [22].

- 2. Study of smart technologies in touristic work

A focus on hospitality workers activities is mostly omitted in tourism studies, swallowed up by the customer-tourist perspective. Tourism studies about workers are mainly considering a global perspective on employment transformation. Some research [23,24] pointed the risk of unemployment generated by robots, AI systems or automation technologies. However, Ivanov (2020) [25] shows more contrasting results. He put forward the opportunity of tasks and jobs reorganisation through a three-step temporal process: “Elimination-Reallocation-Creation”. This later study concerns tasks reorganisation initiated by the adoption of Robotics (R), Artificial Intelligence (AI) or Service Automation (SA) (RAISA technologies). Finally, studies on workers are mainly concerned with the perception of hotel technology use from the perspective of hotel employees. In order to embrace the technology adoption trend in hotels, it is of great necessity to understand the perception of hotel employees, since they are the daily users [26, 27]. Nevertheless, some research are exploring the effects of technologies on work in other professional sectors. An interesting example comes from the journalistic sector [28]. Using a comprehensive ethnographic and ergonomic approach, based on the SCOT (Social Construction of Technology) theory approach, the author analyses the process of designing a journalistic AI to automated text production. Results indicate paradoxical effects: the issues concern the changes in work activity, new forms of task allocation between humans and AI systems, as well as changes in the labour market.

- 3. Chatbot in hotel industry

AI conversational agent (chatbot) refers to a user intention‑recognition system powered by machine learning, which is a disembodied agent, such as a voice-activated virtual assistant [29] and virtual recommendation agent. They are different from the hard-programmed assistants that only conduct repetitive work without learning ability. Nowadays, AI conversational agent are used in a variety of frontline services in tourism and hospitality settings [30, 31]. For instance, this technology can be applied to the process of customer information, to guide tourist customers in the booking process or be a travel partner [32, 33]. A chatbot enables communication between technological services and customers, offering a written response with simulated human language [4,5]. Conversational agents aim to provide a new entry point for customer relations or to assist operators. They are also part of the economic stakes and tend towards greater profitability, with a reduction in the number of human staff, savings on design or even a gain in productivity with humans who could concentrate only on so-called complex tasks [34]. Chatbots are used in different service contexts, tourism recommendation or hotel booking [35]. Several hotel groups have generalised these innovations according to internal development (e.g., conversational agents Phil Welcome for the Accor group, Ivy for Radisson etc.), while other hotel structures, often smaller, collaborate with specialised suppliers in conversational Artificial Intelligence for the hotel market (e.g., Quicktext, etc.). One of the advantages of the chatbot is that it provides a 24‑hour response to the customer. However, this interaction facilitation has been studied more in activity support contexts (e.g., jurist support, call centers support etc.). To our knowledge, its use has not been studied in activities where reception of customers represents the most visible part of the activity. The objectives of this research is to understand how workers articulate these uses while the demand for flexibility is increasingly marked. How, in reception conditions where the variability and uncertainty of the customer flow is high, is it possible to make efficient use of a chatbot designed on the principle of instantaneity? The introduction of chatbots raises questions ranging from the possible modes of cooperation between humans and robots (task sharing, autonomy or subordination of workers to robots; existence of new tasks, possibilities of more sustainable work situations or, on the contrary, impoverished work) but also on how to make the technology evolve..

2. Method

2.1. Theorical basis

For this case study, a systemic approach was elaborated with various methods and tools. The approach is based on grounded research, oriented by the theory of mediated activities. The outcomes of Grounded Theory [36] can lead to three different contributions: theories, models or rich descriptions (e.g., narratives of empirical observations without abstraction). We have oriented the data collection towards a “rich description”. The choice of grounded theory is in accordance with currents oriented on the activity, ergonomics and the development of systemic models oriented by a global view of problematic or uncertain situations [37].For data collection, we used semi-structured interviews and the “UX curve” method (appendix A.2). These methods are in line with our objectives and are often used to facilitate the interviewees’ explanations. Participants were interviewed about the technologies used in their hotels, and technologies were categorised based on the RAISA classification model [38] with a focus on chatbots. They were first asked a serie of questions regarding the « look-alike method of instruction » and were later asked to “Think Aloud” duringUX curve handover [39,40]. The UX Curve method is a qualitative method and has been developed to study User Experience (UX). User experience can be defined as « a person’s perceptions and responses that result from the use or anticipated use of a product, system or service ». In other words, according to the norm ISO 9241-210, it refers to the set of perceptions, feelings, emotions and behaviors caused by technology usage (before, during or after). The UX curve were used to support interviews in an exploratory approach. This method helps to evaluate retrospectively technology usage and user experience [41] by asking the interviewees to drawn several curves in relation to the general evaluation of the chatbot, stimulation level, ease of use and frequency of use. Each UX curve is a schematic representation drawn by the user that reflects the evolution of his/her appraisal on a given subject. The curve starts from the first use of the technology and ends at present day.

2.3.Context

Data were collected in Belgian hotel structures from October 2020 to March 2021. Due to the covid‑19 crisis, participants were interviewed at their workplace or online via virtual platforms, such as Microsoft Teams or Skype. Participants worked either in small and medium-sized enterprises (SME) or in important hotel companies. In general, hotels are structured around different hierarchical figures: the general manager and his assistant general manager (who is mainly in charge of the daily management) constitute the strategic workers; operations manager whose activity concerns the global efficiency; the proximity manager, including the reception manager (who ensures the proper functioning of the reception service), constitute the operational staff with the receptionists. The design worker provides the chatbot technology and is responsible for its development. Please note that this is a purely theoretical description; each interviewed hotel has its own structure and deviates from the general structure presented here. We have classified the workers according to their real activity and not according to the job title. The study focuses on different stakeholders (Figure 2). These actors belong to (i) Operational : receptionist (R), operation manager (OM), assistant general manager (AGM); (ii) Strategy : general manager (GM); (iii) Design : designer (D) (Table 1).

| Levels | Business Lines (Genre, Age) | Interviews (type) |

| Strategy workers | GM : General Manager (Man, 40) Hotel 1 AGM: Assistant General Manager (Woman, 34) (UX curve) Hotel2 | Interviewee1 1h + 50 min Interviewee5 1h 25 min |

| Operation workers | OpM1: Operation Manager 1 (Woman, 30) (UX Curve) Hotel 1 | Interviewee2 1h + 50 min |

| R1: Receptionist 1 (Woman, 36) (UX Curve) Hotel 1 | Interviewee3 1h 35 min | |

| OpM2 : Operation Manager 2 (Woman, 33) Hotel 2 | Interviewee 6 1h15 min (virtual) | |

| R2: Receptionist 2 (Woman, 28) Hotel 2 | Interviewee7 50 min | |

| Design workers | Designer (Man, 30) Hotel 1 | Interviewee 4 40 min + 30 min (virtual) |

- 2.4. Data collection & analysis

Qualitative data were collected through face-to-face semi-structured interviews. All the interviews were recorded and transcribed. We conducted seven interviews in French. UX curves were used to support three interviews. All interviews were fully transcribed for analysis. Interviews were first subjected to global reading. Then, a second cycle coding began to “organise, synthesise, and categorise codes” [42]. As a result, a more focused thematic analysis was carried out around the following topics about chatbots: (1) Motivations for adoption and representation, (2) Reorganization of work activity, (3) Work design, (4) Employment. Some verbatim are presented in appendix A.3 for each theme (from table 1 to table 4).

3. Results

The following sections present the results organised around the extracted themes described in the previous section.

- 3.1. Adoption and representation motivation

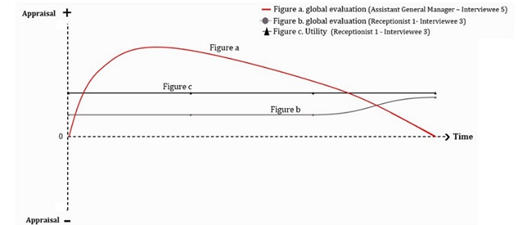

The General Manager and the Assistant General Manager consider chatbot as a way to take over routine tasks and to improve customer experience. These motivations are the main reasons for chatbot implementation (GM-Interviewee1)[Q1]. They perceive chatbots as a gain regarding the quality of work as they provide more accurate information. A designer considers that there are multiple advantages to chatbot use: improving efficiency, reducing workload or improving quality service. Chabot Agent (CA) is considered as a system with the ability to respond quickly and accurately, without being considered as a factor of service customisation (D‑Interviewee4)[Q2]. While it is important to provide a relevant answer quickly, retrieving actionable data is also useful: « The idea is that providing information is not an obstacle. You see, when the client has questions, it does not bother him. We’ll discreetly ask him” (D‑Interviewee4). Operation workers consider technologies as programs or machines that are powered by humans, but also as simple working tools. They make a difference between the personalisation of the service by humans and the use of technologies (OpM2-Interviewee6)[Q3]. While two participants (Receptionist 1 and Assistant General Manager) thought that well-designed chatbots can be more accurate and logically compared with humans, the lack of human presence was seen as the main limitation. An Operation Manager states that the humanistic characteristic of the chatbot makes it as an intelligent technology, compared to automation programs already in use in the hotel (OpM1-Interviewee2). As for the receptionist, the verbalisations associated with the UX curve allow to detect that she does not know how the chatbot works and what is behind the automation of the answers it provides (R1-Interviewee3). For this receptionist, the lack of explanation of how it works and how response decisions are made, does not seem to be related to the global evaluation of the chatbot, which seems to be improving over time (Appendix A.2 – Figure b). In the same way, the chatbot usefulness would increase since it is an evolving technology. However, this result was not found in the UX curve of this receptionist (Appendix A.2 – Figure c). These three results are summarised in the following figure (Figure 2).

- 3.2. Reorganisation of work activity after the implementation of chatbots

- 3.2.1. Activity Transformations for operation workers

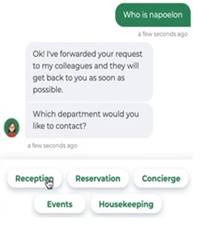

Strategic workers affirm that the hotel reception activities are the first modified activities by the use of chatbots: “There is a bit more attention required on their Dashboard, to check that all the indicators are right. This would really be the heart of the business” (GM-Interviewe1). Operational staff reports fragmented work, which can be a limitation to the use of the chatbot. This difficulty is more important when the shift is done alone at the reception (e.g., evening shift, night shift), because this activity is already fragmented: “When you’re alone, you don’t have much time to talk to the customers because you’ve got others waiting. So, on top of explaining the [chatbot] to them, taking their phone number, looking at the [chatbot] notifications and then adding to that all the requests, the restaurant staff, I find that it adds a huge task on top of that.” (R2-Interviewee7). Chatbots have led to new demands for spontaneity and reactivity from operational staff, especially during the covid‑19 crisis when demand was lower : “Before, any message required an immediate action. Now […] the same goes for chatbots, if a customer picks up the phone, you still have to get back to them quickly.” (GM-Interviewee1). The design worker considers that chatbot is autonomous in 85 % of cases and does not interfere with the activity of operational workers (D-interviewee4). When the chatbot is unable to response autonomously to the customer’s requests, it suggests to transfer their request to another service (housekeeping, reception, etc.), and via e-mail, phone or WhatsApp (Figure 3).

Concerning the operational staff, the chatbot is considered as an additional attention division factor that leads to a higher cognitive workload, as it divides the attention between face‑to‑face and virtual interactions. Operational workers develop strategies to make the devices more responsive to their needs and to keep control of their activities. The customers prioritisation and the management of notifications are illustrations of this. In fact, for operational workers the priority is firstly the face-to-face customer interactions, secondly the customer contact via the official booking channels, and finally the last priority is the customer behind the chatbot. The integration of chatbot is seen as external to their activity purposes (D-Interviewee4)[Q4], leading them to limit its use(OpM1-Interviewee2)[Q5]. When managing interactions with the chatbot, some receptionists find themselves at a loss to know what type of language to adopt (R1-Interviewee 3). Moreover, the lack of clarification on the uses of the chatbot before, during or after the customer journey is an additional stress factor when requests are ambiguous (Figure 4). An illustration of this type of query and the implications for the activity are shown in the following figure.

| Customer request: do you have air conditioning in the room? Involvement in the receptionist’s work activity: In this situation, the question arises whether the request comes from a person listed in the customer database. As this is not the case, she takes over the technology and tries to find out whether the request comes from a customer present in the hotel and whether the request is urgent. In order to formulate her answer, she tells the customers through the chatbot that she prefers to use email, which is more formal and makes it easier to attach images of the rooms and attachments. Finally, in order not to lower the response rate, she must be aware of the channel used by the customer so as not to use the wrong channel, which would lower the customer response rate indicator. |

- 3.2.2. Gestion and supervision of chatbot

Even if it is apparently an autonomous device, a chatbot requires a significant amount of human interventions. The operational staff estimates that the chatbot is 50 % ineffective. Indeed, chatbot parametrisation activity reveals a human investment, questioning the principle of autonomous action of the AI able to learn from its own activity: ”You can put in suggested answers or say you don’t want to put in an answer or say yes or no or define your answer and all that. We will see in the parameters if we can’t readjust the question.” (R1‑Interviewee3). Workers oversee the proper functioning of the chatbot. The principle of autonomous action of AI capable of learning from its own activity is thus not reflected in the results. By its structure, the chatbot is designed to collect customer personal information, offering the possibility of commercial follow-up by the « front-line » staff. Since its integration, the chatbot has not turned any conversation into a reservation. In that way, the conversational agent (CA), in addition to its response capacity, aims to counteract the limitations of the customer relationship management system (CRM system): « In terms of algorithms on customer needs and all that, we are nowhere. » (GM-Interviewee1). As a result, the activity of workers is changing from a service activity to a more commercial process.

- 3.2.3. Feeding chatbot: a new backstage activity

If certain tasks are no longer managed by the staff, we are witnessing the creation of new tasks with workers in charge of feeding and training these systems with data: « The “intentions” that the chatbot will manage must be predefined to frame their detection and propose adapted responses. A human also does the organisation of the data in a classification plan. You must have at least a little bit of supervised learning for the chatbot to get to a decent level, you know. By pooling data from 1000, 2000, 3000 hotels, you just have more capacity to create artificial intelligence models that are interesting.” (D-Interviewee 4). Chatbot management is done behind the scenes on the supplier side, but also directly at the operational level of the hotel structures. Its evolution depends on two conditions: (1) training of the chatbot specific to each hotel by operational staff or receptionists in training: “We have a trainee, for example, who talks to the robot. […] it’s silly things to change but it still takes time. » (OpM1-Interviewee 2), and (2) a monthly collective discussion between General Manager, Operation Manager and designer to readjust its content. The interviews carried out during the covid‑19 period perfectly illustrate this need, which can discredit the hotel if it is not taken into consideration: “There are a lot of hotels that use technological systems for everything, but whose information is very weak, if I use a little text but I don’t put the right information […] it’s useless.” (GM-Interviewee1). Operational workers mentioned a lack of prescription and techno-push attitudes from designers and strategic staff. This induces difficulty for workers to know which tool to use, how to use it and what is the most appropriate work activity to use it for. Another difficulty for receptionists is to know what style of interaction to use when talking to the customer via the chatbot channel (R1‑Interviewee 3).

- 3.3. Organisational design

- 3.3.1. Collective involvement to design the chatbot’s effectiveness.

The chatbot justifies a networked activity structured around technologies: “If someone decides not to use it, it’s a disaster! Because let’s imagine that tomorrow I tell a client, or my colleague, that [chatbot] exists to communicate and that the next day, it’s another colleague who is not at all comfortable with it. He is going to miss a communication with the client.” (R2-Interviewee7)[Q6].The contribution of the UX curves shows it is possible to extend the chatbot global evaluation to several dimensions related, particularly, to each hotel work organisation (Figure 5).

| Researcher : So, it is just the evaluation of the chatbot that you do as a worker so it is not with a vision towards the client. Interviewee 5 : At the beginning, you say, okay, it’s not bad, and then it doesn’t work and so you do it like that [ … ] There were a lot of factors that made it not possible. If you go to another hotel, you’re going to have everyone with well-defined tasks, so you’re going to see a person who is going to fill his or her chatbot all day long, and we’re going to have the same person who takes care of that, who’s going to serve the coffees at the same time as the check-in, so he/she doesn’t have time to do that. Whereas here, as soon as he/she doesn’t have a check-in to do, he/she’ll leave, he/she’ll tidy up and he/she’ll never stay behind his/her computer, so it’s a system that could work very well elsewhere. |

Strategic level considers there are only limited possibilities of actions concerning the improvements of chatbot services, and that it requires a time-consuming and complex process of regulation. For the AGM the average daily time dedicated to the chatbot update is 20 minutes: “I have to analyse the information and then I’m not the one making the changes, so that means I have to recreate the text and send the email back for the text to be done. You add a question, it looks like it takes 5 minutes, but it doesn’t, because it’s a whole process. Maybe I would have done it in 1 minute to change the text directly. On the other hand, no, not at all, you have to contact the people who are going to make the changes.”(AGM1-Interviewee 5).

- 3.4. Effect on employment

Our analysis put forward that stakeholders do not perceive the impacts of technologies in the same way. The design worker interviewee considers that AI conversational agent free up the receptionist’s work: “You have to look at the problem in reverse: it’s not the Chatbot that takes over the human job, but it’s the human who for too long has been doing the job of a machine” (D‑Interviewee4). For the strategy workers, these job evolutions seem less easily perceptible: “So, I really don’t see it as a replacement […] I can’t say that there is more work than before, at the traditional quantitative level, surely not, but surely, there is something? You take away a little bit of work from time to time, but there is a moment where you are not going to be able to take away much […] so, I think that there will still be a sort of transition, an evolution in their everyday job, but it will not be at the expense of the human contact.” (GM-Interviewee1). The operation workers consider different potential transformations of work and are even convinced that they must adopt AI systems and change their work activities to “save” their work (OpM2-Interviewee6)[Q7]. From an operation perspective, operational staff mentioned fear of uselessness and control of their activities (OpM2-Interviewee 6).

- 4. Discussions

Several elements from our results lead our discussion part. Firstly, UX curves revealed that operational workers consider the chatbot use in the light of customer vision, rather than under their own activity. Like many service activities, we observe the importance of the customer in the worker’s discourses.Secondly, we note that technologies are considered relatively differently depending on the stakeholder. Design workers and strategy workers consider chatbot as a facilitating work system and a customer experience improvement. General manager judge chatbots appropriate for repetitive tasks [8,43]. Difference in the representation and perception of real efficiency of technology partly explains the way in which the technology was introduced. We found that there was not any real reflection on the transformations induced on the operational activities. For the designer, the criteria for the chatbot success are to design it as if it did not interfere with the activity, despite the possibility of being able to take control of the system. In terms of relationships, this translates into the subordination of the human being to the response capabilities of the machine.

- 4.1. Passive view of human activity

The situations addressed by the interviewees, mainly end users, refer to a form of passivity, with the human being acting in reaction or because of the machine’s actions, sometimes even completely outside the interaction loop, up to the stage of malfunctioning. This type of automation places human activity in a passive role, which is a source of overreliance and complacency, loss of skills or even a situation awareness deterioration. This relationship had already been found for others AI systems [20]. Many studies have shown the problematic effects of automation when it is based on a theoretical “comparison” of tasks that can be automated by technology. It is also problematic when the tasks are fully automated, leaving the human into the role of “applying” the machines recommendations or decisions. Technology does not directly reduce the workload but transforms it into new requirements (flexibility, etc.) and new tasks as supervision and training of learning chatbots, and the feeding of technological content (commercial follow-up of interactions with the chatbot, etc.) [20]. Another interesting point of this study is the human intelligence for the creation of scalable and contextually adapted systems [44].

- 4.2. A limited autonomy of chatbot and the need for interpersonal mediation between the different stakeholders

Autonomy may refer to a robot’s ability to handle variations in its environment [45]. Our results reveal technologies cannot function completely autonomously without human intervention. Therefore, we can use the theatrical metaphor of “backstage” to describe workers without direct interaction and visibility with the customer [46]. Human activity is necessary to feed the chatbot and ensure its evolutivity, and many interpersonal mediations [47] are needed to achieve a satisfactory response capability. The chatbot, which is supposed to manage the usual interaction cases autonomously, has accumulated limits in its response capacity. According to operational staff, chatbots are not able to learn from their own activity in half the cases. A backstage human investment taken on by operational or strategic staff is necessary to be responsible for feeding and training these systems with data. Contrary to the designer ambitions, chatbot is considered as a new tool to collect information and get to know the customer better. The response rate or the conversion rate of interactions into bookings is not considered as a criterion for keeping the chatbot in business. This dimension differs from other studies in the service sector. The model of interaction aims to collect and centralise usable data. Monitoring of the responses’ quality is not carried out and does not even determine the success of the interaction as this is not the only objective pursued by the chatbot. Another goal is to collect new information (e.g., name, email) about the customer that can be directly used by the operation workers on different channels [29, 30]. It is developed with the aim of getting to know customers better, systematically and on a massive scale [2, 48].

- 4.3.A misguided view of operational activity

The usual techno-push approaches consider the use of AI systems as purely technological projects, without taking into consideration the real activities as support for the organisational design. By not wanting to interfere with activities, some uses of AI systems bring the issue of the human‑machine relationship model to the forefront. It partly explains the failure of AI deployment project [20]. In this context, operational employees may be concerned for their jobs and perceive robots as a threat, although studies have shown that the GM envision robots as support for employees rather than as their substitutes [43]. Another problem is that technology do not share situational awareness. Even if the user mainly takes back the situations ingested by the chatbot, the operator is forced to resituate the request in its context at each use (type of reservation, customer constancy etc.).

- 4.4. Cooperative or integrative vision of activity

Introduction of chatbot results in profound reconfigurations of human activities. The practices of automated communication partially stress the strategic role of the operational professions in charge of the service relationship [49]. This study shows that conversational robots do not replace humans, but that a new division of labour is emerging between human agents and robots. In order to meet informational requirements, hotels are facing the challenge of defining the roles between the chatbot and the face-to-face staff, which is rarely defined upstream of the project. As a result, new requirements are added to the initial work. In line with the managerial problems caused by information systems, the chatbot requires an organisation to redefine its front-line roles in order to satisfy an “urgency of the present” [50], which seems incompatible with the work organisations currently in place. The chatbot effectiveness requires interpersonal mediations, that are very time consuming but also procedural, to achieve an effective modification of the chatbot responses, especially in the context of a hotel chain [47].

- 5.Conclusion: reconfiguring the organisation’s design to build an efficient chatbot

The introduction of technologies has brought a profound rearrangement of the stage and backstage professions. Chatbot is seen as a social innovation [51] on the design and strategy side. From an operational point of view, the study is more nuanced. Indeed, they can be deleterious to the work activity and the service relationship when the conditions of implementation are not thought upstream the conception and have a lack of reflection on the work design. The chatbot can be a service solution in the future but this technological innovation must be associated with managerial and organisational innovation. A reflection on the new organisational possibilities such as mobility, versatility and remote management must be assessed in advance. The deployment of a technology cannot be effective without a global analysis of the work activity context. As prerequisite, the appropriation of smart technologies must be based on a systemic reflection on the activity seen from the point of view from the micro-organisation to the macro‑organisation.

- 5.1.Perspectives

Our analyses lead to several perspectives. Firstly, it is not possible to choose between customer and worker experience. It is rather necessary to take in account both issues: the “customer-centric” perspective and the “user experience” one. This developmental perspective foretells a reversal of the notion of experience for the tourism sector. This implies that the objective of the organisation cannot be the exclusive satisfaction of the final client, but that those who provide the service must also be considered as clients of the work design process and participate in its settings. The reflection on this double challenge of the experience can only be done in a work situation, especially since the service is a space of shared co‑creation. Concretely, chatbot must be designed from the knowledge of operational workers activity. This knowledge must be the basis for work design, which requires taking into account the diversity of work situations encountered and the individual and collective regulations involved in bringing the chatbot to life. The results regarding the lack of understanding for the interviewee3 with, paradoxically, a general increase in the evaluation of the chatbot over time, are in line with some research. The user does not need to know the nuances of artificial intelligence and the structure of the technological system it is manipulating [52]. This result is contrary to Zouinar (2020) [17] who highlights the problems that a low level of knowledge can cause: increasing dependence of the human on the machine and the risk of loss of knowledge and skills; uncertainty and fear for the job for the user who can’t assess the reliability of the proposals made by the machine. These issues are a matter for ergonomics, and solutions must be found both in the training of users and in the design of machines (transparency, explicability and interpretability of intelligent systems). This increase in global evaluation over time can also be explained by the emotional relationship and attachment that develops between the worker and the human characteristics given to the chatbot. Secondly, technology adoption does not mean substitution of the previous ones but is part of a continuity. A diversity of technologies can be found in an activity system [53] oriented towards customer satisfaction and service customisation. It is shown that technological adoption fundamentally depends on the context in which these systems are deployed and their capabilities [54] under multi-instrument conditions. Applying an ergonomic psychology approach to design seems to be a way to enable a new work design. one perspective is to give to operational workers dynamic access to the chatbot’s activity in relevant terms (summary sheet of the answers to the different intentions proposed by the chatbot). The issue is to establish a relationship between the state of the chatbot and the real state of the work in which the user is engaged with complete awareness of the situation.

- 5.2. Limitations

Several limitations are associated with this study. A first limitation is linked to the context, which is necessarily dependent on the covid‑19 crisis, as well as on the type of structure. Due to the small size of our sample and the unique organisational context explained, our results should be taken with caution. In fact, Hotel 2 is a test hotel for the hotel chain, which implies that the strategic level is supporting several technological innovation projects. This investment can lead to fatigue due to the accumulation of piloted projects. UX curves led in this structure may have been impacted by this organisational specificity and the respondents’ experience with the hotel history. Belgian context also influences results essentially derived from interviews. A second limitation we identify is related to data collection mainly conducted without observation. However, it is necessary to mention the contribution of the UX curves to support the verbalisation during the interviews in the covid‑19 crisis. This exploratory study focused on the chatbot accompanied by UX curves and should allow us to understand the activity in future research. It would be interesting to associate these results about chatbot with systemic observation of technologies to better understand receptionist activity in multi-instrumented conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the various Brussels hotel stakeholders and technology providers who participated in the collection of data in the framework of the Cap-SMART (Capacity Development for Monitoring and Controlling the Adoption of Robotics and other Intelligent Technologies in Brussels Tourism) study and global research. This Project funded by Innoviris (agreement number 2018-Anticipate-025). We also thank Ms. A. Aeberhard and Ms. E. Fuscolani for the rereading.

REFERENCES

[1] M. Benedetto-Meyer et A. Boboc, « Accompagner la «transformation digitale»: du flou des discours à la réalité des mises en øeuvre », Travail et emploi, no 3, p. 93‑118, 2019.

[2] T. Pencarelli, « The digital revolution in the travel and tourism industry », Information Technology & Tourism, vol. 22, no 3, p. 455‑476, 2020.

[3] M. Zsarnoczky, « How does artificial intelligence affect the tourism industry? », VADYBA, vol. 31, no 2, p. 85‑90, 2017.

[4] A. P. H. Chan et V. W. S. Tung, « Examining the effects of robotic service on brand experience: the moderating role of hotel segment », Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, vol. 36, no 4, p. 458‑468, 2019.

[5] Y. Choi, M. Oh, M. Choi, et S. Kim, « Exploring the influence of culture on tourist experiences with robots in service delivery environment », Current Issues in Tourism, p. 1‑17, 2020.

[6] V. W. S. Tung et R. Law, « The potential for tourism and hospitality experience research in human-robot interactions », International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 2017.

[7] O. H. Chi, D. Gursoy, et C. G. Chi, « Tourists’ Attitudes toward the Use of Artificially Intelligent (AI) Devices in Tourism Service Delivery: Moderating Role of Service Value Seeking », Journal of Travel Research, 2020.

[8] S. Ivanov et C. Webster, « Conceptual framework of the use of robots, artificial intelligence and service automation in travel, tourism, and hospitality companies », in Robots, Artificial Intelligence, and Service Automation in Travel, Tourism and Hospitality, Emerald Publishing Limited, 2019.

[9] P. Mura et R. Tavakoli, « Tourism and social capital in Malaysia », Current Issues in Tourism, vol. 17, no 1, p. 28‑45, 2014.

[10] J. Reis, N. Melão, J. Salvadorinho, B. Soares, et A. Rosete, « Service robots in the hospitality industry: The case of Henn-na hotel, Japan », Technology in Society, vol. 63, 2020.

[11] X. Lv, Y. Liu, J. Luo, Y. Liu, et C. Li, « Does a cute artificial intelligence assistant soften the blow? The impact of cuteness on customer tolerance of assistant service failure », Annals of Tourism Research, vol. 87, p. 103-114, 2021.

[12] N. Le Ru, « L’effet de l’automatisation sur l’emploi: ce qu’on sait et ce qu’on ignore », La Note d’analyse–France Stratégie,(49), p. 1‑8, 2016.

[13] P. Tubaro, A. A. Casilli, et M. Coville, « The trainer, the verifier, the imitator: Three ways in which human platform workers support artificial intelligence », Big Data & Society, vol. 7, no 1, 2020.

[14] C. Esteban, « Construire la «compréhension» d’une machine », Reseaux, no 2, p. 195‑222, 2020.

[15] E. Morin, Introduction à la pensée complexe. Média Diffusion, 2015.

[16] D. Harrisson et M. Vézina, « L’innovation sociale: une introduction », Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, vol. 77, no 2, p. 129‑138, 2006.

[17] M. Zouinar, « Évolutions de l’Intelligence Artificielle: quels enjeux pour l’activité humaine et la relation Humain-Machine au travail? », Activités, no 17‑1, 2020.

[18] K. Anastasia, K. Julia, K. Elena, et S. Eldar, « Discrimination and Inequality in the Labor Market », Procedia Economics and Finance, vol. 5, p. 386‑392, 2013.

[19] M.-E. Bobillier Chaumon, « Exploring the Situated Acceptance of Emerging Technologies in and Concerning Activity: Approaches and Processes », Digital Transformations in the Challenge of Activity and Work: Understanding and Supporting Technological Changes, vol. 3, p. 237‑256, 2021.

[20] T. Gamkrelidze, M. Zouinar, et F. Barcellini, « The “Old” Issues of the “New” Artificial Intelligence Systems in Professional Activities », Digital Transformations in the Challenge of Activity and Work: Understanding and Supporting Technological Changes, vol. 3, p. 71‑86, 2021.

[21] C. Dejoux, « Comment l’intelligence artificielle s’ attaque au manager? », Management & Datascience, vol. 4, no 3, 2020.

[22] A. S. Miner, L. Laranjo, et A. B. Kocaballi, « Chatbots in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic », NPJ digital medicine, vol. 3, no 1, p. 1‑4, 2020.

[23] K. Dengler et B. Matthes, « The impacts of digital transformation on the labour market: Substitution potentials of occupations in Germany », Technological Forecasting and Social Change, vol. 137, p. 304‑316, 2018.

[24] C. B. Frey et M. A. Osborne, « The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation? », Technological forecasting and social change, vol. 114, p. 254‑280, 2017.

[25] S. Ivanov, « The impact of automation on tourism and hospitality jobs », Information Technology & Tourism, vol. 22, no 2, p. 205‑215, 2020.

[26] T. G. Kim, J. H. Lee, et R. Law, « An empirical examination of the acceptance behaviour of hotel front office systems: An extended technology acceptance model », Tourism management, vol. 29, no 3, p. 500‑513, 2008.

[27] S. Sun, P. C. Lee, R. Law, et S. S. Hyun, « An investigation of the moderating effects of current job position level and hotel work experience between technology readiness and technology acceptance », International Journal of Hospitality Management, vol. 90, p. 102633, 2020.

[28] L. Dierickx, « Journalists as end-users: Quality management principles applied to the design process of news automation », First Monday, 2020.

[29] I. Tussyadiah et G. Miller, « Perceived impacts of artificial intelligence and responses to positive behaviour change intervention », in Information and communication technologies in tourism 2019, Springer, 2019, p. 359‑370.

[30] S. H. Ivanov, C. Webster, et K. Berezina, « Adoption of robots and service automation by tourism and hospitality companies », Revista Turismo & Desenvolvimento, vol. 27, no 28, p. 1501‑1517, 2017.

[31] S. Park, « Multifaceted trust in tourism service robots », Annals of Tourism Research, vol. 81, 2020.

[32] M.-H. Huang et R. T. Rust, « Artificial intelligence in service », Journal of Service Research, vol. 21, no 2, p. 155‑172, 2018.

[33] S. Ivanov, U. Gretzel, K. Berezina, M. Sigala, et C. Webster, « Progress on robotics in hospitality and tourism: a review of the literature », Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 2019.

[34] J.-B. Le Corf, « L’organisation homme-machine de la communication automatisée d’entreprise dans le capitalisme: le cas des robots conversationnels », Communication management, vol. 14, no 2, p. 35‑52, 2017.

[35] S. Parmar, M. Meshram, P. Parmar, M. Patel, et P. Desai, « Smart hotel using intelligent chatbot: A review », International Journal of Scientific Research in Computer Science, Engineering and Information Technology, vol. 5, no 2, p. 823‑829, 2019.

[36] B.G. Glaser et A.L Strauss, The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New Brunswick, NJ: Aldine Transaction, 2010.

[37] J. Petit, « Intervention sur l’organisation : concevoir des dispositifs de régulation pour un travail plus démocratique. » Sciences de l’Homme et Société. Université de Bordeaux, 2020.

[38] C. Webster et S. Ivanov, « Robotics, artificial intelligence, and the evolving nature of work », in Digital Transformation in Business and Society, Springer, 2020, p. 127‑143.

[39] E. Charters, « The use of think-aloud methods in qualitative research an introduction to think-aloud methods », Brock Education: A Journal of Educational Research and Practice, vol. 12, no 2, 2003.

[40] D. W. Eccles et G. Arsal, « The think aloud method: what is it and how do I use it? », Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, vol. 9, no 4, p. 514‑531, 2017.

[41] S. Kujala, V. Roto, K. Väänänen-Vainio-Mattila, E. Karapanos, et A. Sinnelä, « UX Curve: A method for evaluating long-term user experience », Interacting with computers, vol. 23, no 5, p. 473‑483, 2011.

[42] S. J. Tracy, Qualitative research methods: Collecting evidence, crafting analysis, communicating impact. John Wiley & Sons, 2019.

[43] S. Dogan et A. Vatan, « Hotel managers’ thoughts towards new technologies and service robots’ at hotels: A qualitative study in Turkey », Co-Editors, p. 382, 2019.

[44] R. Hindi, L. Janin, C. Berthet, J. Charrié, A.-C. Cornut, et F. Levin, « Anticiper les impacts économiques et sociaux de l’intelligence artificielle », mars, 2017.

[45] S. Thrun, « Toward a framework for human-robot interaction », Human–Computer Interaction, vol. 19, no 1‑2, p. 9‑24, 2004.

[46] G. Pinna et B. Réau, « Service de luxe et classes sociales », Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, no 5, p. 72‑77, 2011.

[47] M. Gras Gentiletti, M. Fréjus, G. Bourmand, et F. Decortis, « Médiations interpersonnelles et évolutivité de systèmes à base d’IA Un exemple à partir de l’appropriation de chatbots en entreprise », Paris, 2021, p. 304‑309.

[48] M. Benedetto-Meyer, « Des statistiques au cøeur de la relation clients: l’accès aux «données clients», leur effet sur l’organisation du travail et les relations clients/vendeurs en boutique », Sociologies pratiques, no 1, p. 49‑61, 2011.

[49] G. Jeannot et I. Joseph, Métiers du public. Les compétences de l’agent et l’espace de l’usager. CRNS Editions, 1995.

[50] B. Guyot, « Mettre en ordre les activités d’information, nouvelle forme de rationalisation organisationnelle », Les Enjeux de l’information et de la communication, vol. 2002, no 1, p. 49‑64, 2002.

[51] G. Mulgan, « The process of social innovation », Innovations: technology, governance, globalization, vol. 1, no 2, p. 145‑162, 2006.

[52] OECD . Preparing the tourism workforce for the digital future, OECD Tourism Papers, n°2021/02, OECD publishing, Paris,2021.

[53] Y. Engestrom, H. Kerosuo, et Y. Engeström, « From workplace learning to inter-organizational learning and back: the contribution of activity theory », Journal of workplace learning, 2007.

[54] J. Arnoud, « Conception organisationnelle: pour des interventions capacitantes », PhD Thesis, 2013

Appendices

A.1 Look-alike method

| Phase 1 look-alike interview | Interviewee: « Suppose I am your look-alike and tomorrow I find myself alone in your place in reception. It is expected to be a high occupancy rate of almost 100 %. What are the instructions, what are the tips you should give me so that no one notices the substitution and I can handle the shift without any problems?” Relaunch interviewee : 1/ So by the time I get there what do I need to do again. 2/ What tools do I need to use to know what I have to do. 3/ What tool do I use to do what I have to do. 4/ When there are no physical demands, what and who do I have to pay attention to. 5/ It is break time, I have to go eat, how can I maintain a quality of reception? |

| Phase 2 support for UX curves | Interviewee: 1/ Do you feel that the chatbot brings a change in your workload (in which direction is the relationship?)? 2/ Do you feel that the chatbot takes a part of your work today or does it give you more added value with customers as a receptionist? 3/ Do you sometimes have to follow up on customers via the information collected by the chatbot by phone? How do you perceive this activity, do you think it is part of your role as a receptionist? 4/ Are you aware of how the chatbot work? Do you participate in the evolution of this system? If yes, in which way? |

A.2 UX curves

A.3 Verbatim reports dedicated to the themes

| Table 1 – verbatim from the interviewees for the theme motivation | |

| 1.Motivation adoption | Q1: For me all of these choices are really adding value to the customer experience while often making the receptionists’ job easier. (GM-Interviewee1) Q2: I don’t like the term personalisation because in fact the Chatbot’s answers don’t change. (D-Interviewee4) Q3: We have many tasks that the machine cannot perform. So yes, it is a tool, and it helps, but if I unplug it, I will not miss it. On the other hand, if I remove my receptionists, we will really feel the difference. A machine will never replace a person that is for sure. It is there to help but not to replace. (OpM2-Interviewee 6) |

| Table 2 – verbatim from the interviewees for the theme activity | |

| 2.Activity | Q4: We try that the receptionist doesn’t even have to read the conversation, we only put the conversation download if it’s necessary […] we try […] to not integrate into the life of the receptionist (D-Interviewee 4) Q5: I decided that we would only receive a notification when the customer starts a conversation with Velma [chatbot] and that way, when we don’t have much to do, we can open the email and see directly what Velma answers. In addition, even catch up directly if Velma answers badly or as I told you if we see it later, we take care of it and if the customer has left and well, we can always send him an email. (OpM1-Interviewee 2) |

| Table 3 – verbatim from the interviewees for the theme work design | |

| 3.Organisational design | Q6: In fact, I find that all the installations of these new technologies require a huge follow-up […] if it’s not collectively shared you going to miss a communication with the client. (R2-Interviewee7) |

| Table 4 – verbatim from the interviewees for the theme employment | |

| 4.Employment | Q7: I love my job, but I understand that we are going to witness a completely different hotel and catering sector, everything will be automated and adapted to this digitalization. Managers will have to adapt […] to be useful in the system. (OpM2–Interviewee6) |

[1] Neologism used to designate that the activity depends more and more on actions carried out by mediating technological systems.

12 Responses

Hi there! I know this is kinda off topic however I’d figured I’d ask.

Would you be interested in exchanging links or maybe guest writing a blog

post or vice-versa? My blog addresses a lot of the same topics as yours and I believe we

could greatly benefit from each other. If you are

interested feel free to send me an e-mail. I look forward to hearing

from you! Excellent blog by the way!

Thanks a lot Alberta

It is an anteresting proposition. Could you tell me more about the purpose of your blog? Have you got a link ?

Have a nice day,

CAP-SMART team

Hi friends, good piece of writing and pleasant arguments commented at this place, I am really enjoying by these.

Hello Erick,

Thank you so much for your message and for your interest in our research on chatbots.

Yours faithfully,

CAP-SMART team

Highly descriptive blog, I enjoyed that a lot. Will there be a part 2?

Hello, thank you very much

We will try to publish a follow-up to this study in the coming year.

Yours faithfully,

CAP-SMART team

Very nice post. I simply stumbled upon your weblog

and wished to say that I’ve truly loved surfing around your weblog posts.

In any case I will be subscribing for your rss feed and I am hoping you write again soon!

Hello, thank you very much for your very encouraging message.

Yours faithfully,

On behalf of the entire capsmart team

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve visited this blog before but

after browsing through a few of the articles I realized it’s

new to me. Anyhow, I’m certainly pleased I came across it and I’ll be book-marking it and checking back often!

thank you very much Florentina, do not hesitate if you have specific questions about our writings

Yours faithfully,

CAP-SMART team

Hello,

I hope I’m not bothering you, my name is Tyrell and I see that you own ulb.be. I noticed a few errors on your website that could be causing you to lose some traffic & customers.

Do you have 5 minutes to speak about this?

Hope to talk soon!

Tyrell

Hello Tyrell

We are happy to discuss and exchange ideas.

I am available at pierre.flandrin@ulb.be. I will send you a phone number on your email adress.

Have a nice day,

Pierre